If you went skydiving, would you first ask for scientific evidence from a randomized trial that a properly functioning parachute prevents injury before you’d consider using one during your freefall? Probably not.

In fact, no such study exists. Of course, some people without a parachute have survived a freefall from extraordinary heights without injury, and others have sustained injuries even when using a parachute. But it’s clear that you’d use a parachute when skydiving, even without a single randomized trial to prove its effectiveness. Yet, when it comes to medicine, clinicians may be reluctant to employ any intervention without rigorous scientific evidence for its efficacy.

The need for sound evidence evolved from a history of medicine that’s littered with practices that were later abandoned after scientific scrutiny showed that they were ineffective, perhaps even harmful.

As such, we are among the many who would agree with the general concept of “evidence-based medicine.” However, when it comes to patient safety, there are significant obstacles to this approach. (see here)

Because Evidence Based Medicine (EBM) places all of the emphasis on clinical trials, it forgets to ask the first, most basic question of all: does the idea make sense? Through this EBM can be used inappropriately as a tool to maintain the status quo. Evidence Based Medicine was never designed to assess the plausibility of basic science e.g. the effects of gravity on someone jumping out of a plane.

Remember, science helps us understand how things are. A more beneficial way to consider evidence is through the framework of Science Based Medicine (see here). Science Based Medicine’s philosophy is that we ought to consider prior probability and plausibility from basic science when determining if a claim is real enough to study. If the claim passes this test, then it should be studied with proper, well-executed clinical research. However in delaying the adoption of obviously better interventions, while waiting for clinical research, we may leave patients at unnecessary risk (see here).

Consider too, is it really the evidence from multicentre randomised controlled trials (RCTs) which ultimately lead us to adopt a better practice?

Take the example of ultrasound use when inserting central lines – many doctors had honed their skills over years, inserting central lines without the need for ultrasound. Some were then reluctant to use ultrasound when it became available – they hadn’t needed it before so why should they use it now?

What was the level of evidence which led to change in practice? Was it a multicentre RCT or was it a collection of other influential issues:

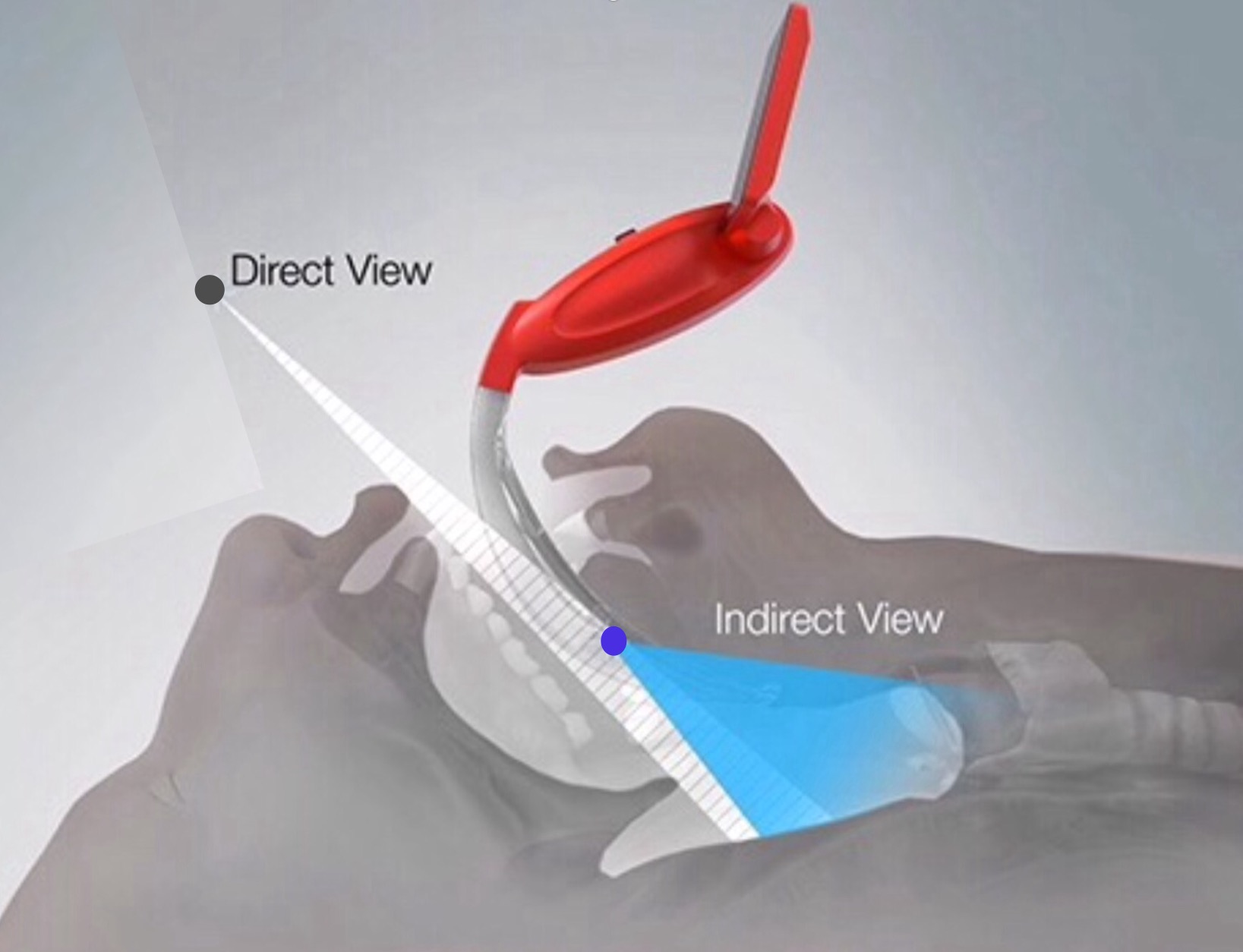

– The basic scientific notion that it’s better to be able to see what one is doing

– A series of heuristic stories of patients succumbing from complications which may have otherwise been avoided*

– Policies introduced obligating the use of ultrasound when it is available (see here)

– A gradual change in culture, and an adoption by sufficient numbers such that those not using ultrasound perhaps begin to feel estranged

– Retirement of those unwilling to change, those who stoically prevent change no matter what, those who Dr Jonn Hinds may have labelled as ‘Resus Wankers‘.

We do not live or practise in a laboratory, nor within the boundaries of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. We live in a real world with patients who are also people. Intuition, clinical experience, and pathophysiologic rationale are indeed important tools, along with evidence-based literature, with which to discern the best care for our patients. To honour such a breadth of perspective, however, requires us to loosen our tenacious grip of currently accepted doctrines of EBM as the definitive measure of good clinical practice. For in the end, it is really our common sense, nurtured by education, experience, intuition, and rationale, that is always our ultimate measure of evidence—in medicine as in life itself. (See Here)

When better (in accordance with basic science) interventions become available we should perhaps be more ready to adopt them.

Certainly lack of evidence must not be used inappropriately to stoically defend the status quo – for in the end it is our patients who suffer.

*It is with interest to note that one of the main presenters of NAP4 data routinely uses a video laryngoscope for intubation. Perhaps he has been influenced by an understanding of Science Based Medicine and exposure to numerous stories of patient demise from difficult tracheal intubation.

Basic Science:

5 Comments