Australia’s drugs and medical devices watchdog has denied it is too close to the industry or that receiving funding from health and medical companies is a conflict of interest, after its independence was questioned by health experts.

On Monday Dr Wendy Bonython from the University of Canberra’s Health Research Institute told Fairfax Media that the Therapeutic Goods Administration’s [TGA’s] industry funded model of regulation needed a complete overhaul, including “a clear break between the regulator and the parties they’re trying to regulate”.

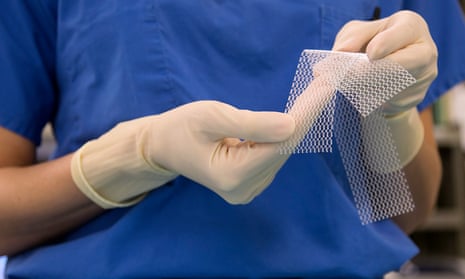

Bonython said accepting fees from industry was unacceptable in the wake of the transvaginal mesh scandal that saw the TGA approve meshes for use in treating prolapse despite a lack of evidence for the safety and efficacy of the products. Thousands of women who received the meshes have reported complications including severe pain and damage to nerves and nearby organs, including the bladder and bowel.

On Tuesday Ken Harvey, a professor of public health and preventive medicine at Monash University, criticised a decision by the TGA to allow a supplement company to promote a herbal remedy as helpful in relieving the symptoms associated with an enlarged prostate, despite scientific evidence to the contrary. Harvey told Guardian Australia it was “another example of them [the TGA] being very helpful to industry while being ineffective from a consumer protection point of view”.

The criticisms prompted the TGA to release a statement on Wednesday saying it “totally rejects claims” of a “too close relationship between regulator and industry because of this funding model”.

“While fees received, for example, for the evaluation of a product are used to fund staff time on evaluation of that product, they are not refunded if the application is rejected or withdrawn,” the statement said.

“Industry has no say whatsoever in how TGA spends the revenue it receives from other industry charges. This system has been in place for more than 20 years and there has been no evidence of any sort of regulatory capture.”

In regards to transvaginal meshes, the TGA said it could only make decisions based on evidence available at the time. In 2008 an expert committee found the reported rate of complications from the meshes was low, with complications closely linked to the skill and training of the surgeon and the patient selection.

“So at that time it would have been inappropriate to implement some of the measures that have been introduced more recently,” the TGA said.

In October last year the TGA announced it was reclassifying transvaginal meshes as “high risk” following post-market reviews conducted in 2010 and 2013, and that this new classification and additional regulations around the devices would commence in December next year with a staged transition period. From July 2012 to 1 June 2016, the TGA received 99 adverse events reports involving urogynaecological surgical meshes, with pain and erosion the most frequent complaints. The TGA acknowledged adverse events were likely underreported.

“Other medicines and device regulators internationally also are fully or significantly funded by industry fees and charges and operate in the same way,” the TGA statement said. “This takes the burden off the taxpayer for such time-consuming scrutiny.”

But, in a complaint to the TGA, Harvey accused the regulator of being “disingenuous”.

“Regardless of whether the regulator is funded by industry fees or the government, the consumer pays, either through higher prices on therapeutic goods or increased taxation,” he said.

“Second, how many other therapeutic goods regulators are 100% funded by industry? The benefits of industry funding are that the regulator is not constrained by cutbacks in government budgets, efficiency dividends and other constraints. The downside is that industry has a greater say in how its fees are used and there is an increased risk of regulatory capture.”