In doing nothing we have still made a decision.

Bystander Effect: the greater the number of people present, the less likely people are to help.

The bystander effect was first demonstrated following the murder of Kitty Genovese in 1964. The New York Times published a report conveying a scene of indifference from neighbors who failed to come to Genovese’s aid, claiming 38 witnesses saw or heard the attack and did nothing.

Psychologists launched a series of experiments resulting in one of the strongest and most replicable effects in social psychology.

Is healthcare safety suffering the ‘Bystander Effect’?

Several factors contribute to this phenomenon:

Diffusion of Responsibility:

When so many are in charge no one is. Where there are many observers, individuals do not feel as much pressure to take action.

There are numerous groups involved with healthcare safety at international, national, state, regional, hospital and individual department level. Just looking at some of those involved in NSW we have (apologies for acronyms) ACQHSC, TGA, CEC, ACI, AMA, ASA, ANZCA….

Each of these groups are made up of further subgroups of individuals. Further still these subgroups are not static – a constant flux of staff members into different roles stifles effective response.

Acceptable Behaviour:

The need to behave in correct and socially acceptable ways. When other observers fail to react, individuals often take this as a signal that a response is not needed or not appropriate.

If pressed on an issue individuals or groups may introduce barriers allowing them to delay action sufficiently, in effect not acting at all, thus maintaining perceived acceptable behaviour.

A common example of a delaying tactic in healthcare safety:

‘The information we’ve received hasn’t been delivered in an appropriate way. We require a formal letter / the issue to be reported directly into our system before we’re obliged to act.’

Depersonalisation:

Research demonstrates onlookers are more likely to act if they have a personal connection to the victim.

Unfortunately the structure of our incident reporting systems is such that those who can access the data are the furthest removed from the emotion of the front line. The deaths and morbidity appear as statistics – not as people with families and extensive life relationships.

Ambiguity:

Researchers have found that onlookers are less likely to intervene if the situation is ambiguous. In the Kitty Genovese case many witnesses reported it sounded like a “lover’s quarrel,” and claimed to not realise the young woman was being murdered.

Lack of transparency in incident reporting systems may perpetuate ambiguity – is the problem really as bad as people are suggesting.

For example: ‘Indistinct pourable chlorhexidine has been registered by the TGA, it’s been present in hospitals for some time, surely if it’s such a big problem we would have heard about it before now.’

Self Preservation:

For some bystanders in the Kitty Genovese murder what they experienced would not have been ambiguous. Yes, someone was being stabbed to death in front of them. Self preservation may have hindered their want to act – they too may then be at risk.

To bring about effective safety change where previously there’s been none requires challenging the status quo, ‘rocking the boat’, in effect potentially threatening ones own career – upset the wrong people and the consequences could be grave. Many of us have mouths to feed and mortgages to pay – are we really going to put that at stake in a futile attempt to change something no one’s been able to change before?

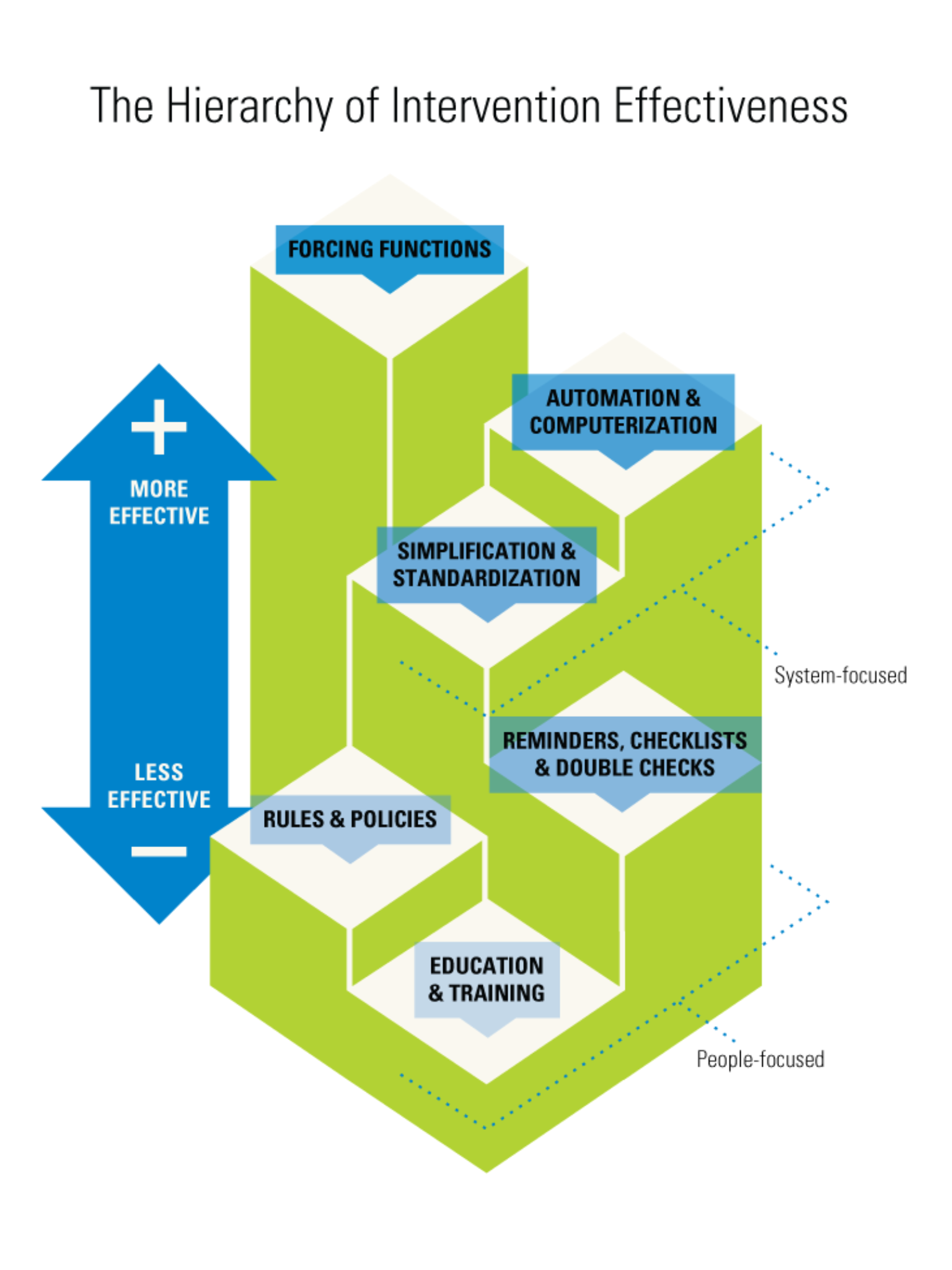

Governing bodies often resort to interventions which are safe for them. They shy away from, for example, recalling an unnecessary workplace hazard. They may fear legal ramifications from the manufacturer and resultant heat from their employer (the health minister). Often instead the governing body may write a policy or instrument further education in a vain attempt to avoid the hazard.

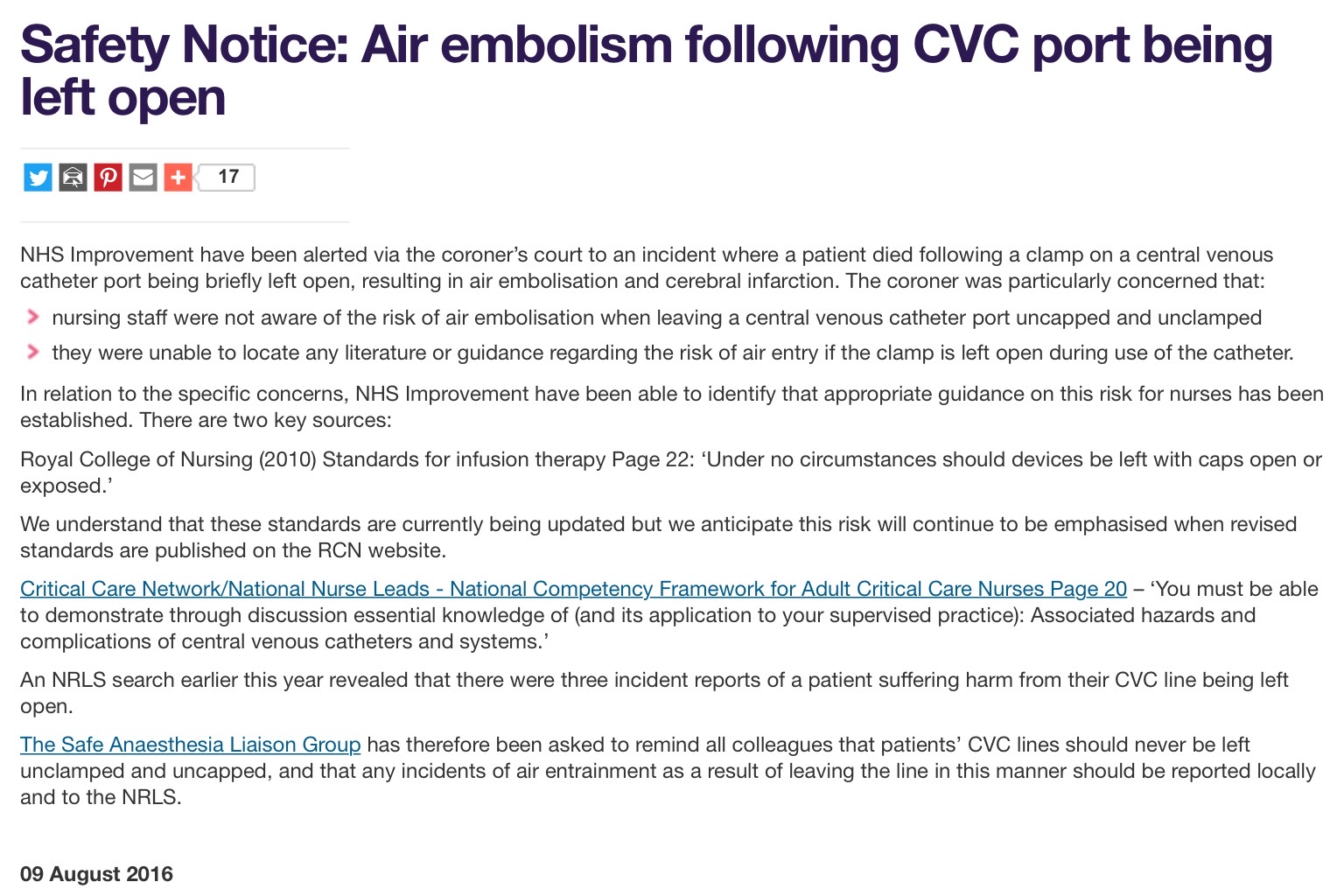

This response from the RCOA to yet another central line air embolism death is a prime example:

Instead of taking the opportunity to replace hazardous central lines (see here) an alert has been disseminated which will have little effect.

Governing bodies need to understand the human factors approach and have the courage to introduce effective solutions for patient safety.

4 Comments